On this day in history, July 12, 1949, Apogee was born.

The History of Apogee

Two glass workers and a car salesman pooled their money and leased part of an old General Tire store, and on July 12, 1949 Harmon Glass Company was born. In 1950, a young attorney, Russ Baumgardner, helped Harmon to its feet by investing $10,000 in the new venture. The business soon became his passion.

Glen Straub, Orville Peterson, and Kenneth Hintz founded Wausau Metals in 1956. Sharing space with a brewery, they started out by manufacturing aluminum ventilators for use with glass blocks – a popular construction material in the ’50s. Eventually, the company began producing custom windows for schools and commercial buildings.

In 1968, for $2 million, Harmon Glass acquired Wausau Metals Corporation, which was as big as Harmon itself. Upon purchase of Wausau Metals, Glen Straub, Wausau Metals’ founder and principal manager, announced he was moving to Las Vegas. Baumgardner’s partner Larry Niederhofer offered to move to Wausau for six months and run the new business.

Apogee Enterprises, Inc. was founded in 1968, by Baumgardner, as a holding company to oversee a growing number of profit centers. Baumgardner took the new entity’s name from an investment club called “Apogee” to which he once belonged. He paid only $1 for the right to use the designation.

In 1969, a young windshield manufacturer salesman, Jim Martineau, hatched a plan with Baumgardner to set up a glass fabricating operation. On September 22, the Apogee board approved, and Viracon was born. Viracon was one of the nation’s first regional glass fabricators. It built its success and reputation by combining many fabrication processes under one roof, just as Martineau said it would.

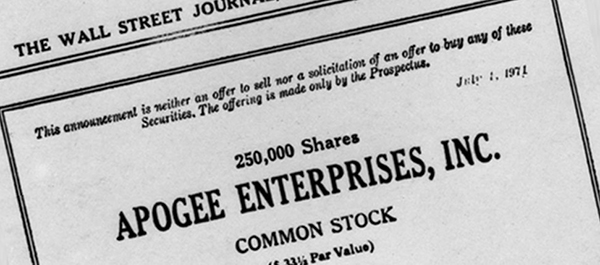

In 1971, Apogee’s stock prices were surging. On June 30, the company and certain shareholders sold 250,000 shares, and Apogee became a public company.

In 1971, Apogee’s stock prices were surging. On June 30, the company and certain shareholders sold 250,000 shares, and Apogee became a public company.

In 1973, Reynolds Metals Company, a large aluminum maker, was using relatively new plastic, polyurethane, to create an effective thermal barrier in its line of residential windows. After licensing the approach from Reynolds, Wausau Metals modified it and then designed its own equipment for pouring the polyurethane into aluminum window frames. Wausau’s Thermo-barrier windows were the first poured-in-place polyurethane systems in commercial windows.

In 1974, as gas prices soared, fuel-efficient Japanese and other foreign automobiles began arriving in America in record numbers. Their replacement windshields had to come from abroad – until Viracon stepped into the niche by forming a new windshield manufacturing operation called Curvelite. In less than four years, Curvelite became the nation’s largest fabricator and distributor of foreign car replacement windshields.

In the early ’70s, few companies recognized Harmon Glass as a contract glazing business: it was known as an auto glass company. Using the name Harmon Contract, the barriers to architectural glazing projects came tumbling down, and by 1974, profits had doubled.

In 1975, windshield replacement rates fell as speed limits came down. In looking for ways to grow, Harmon Glass formed a task force to investigate muffler replacement. Eventually several Harmon Glass – Midas Muffler shops opened. Harmon Glass and Midas shared overhead and labor, making expansion in to smaller communities a viable option.

In 1976, Apogee acquired Milco Specialties, Inc., a sliding and double-hung window manufacturing company as a result of Wausau Metals being pressed by its many customers to provide other products. Milco, a tiny company located in Rochester Michigan, had become one of the nation’s most well-respected manufacturers of horizontal rolling and double-hung windows. Milco’s owner wanted to retire and made Niederhofer an offer he could not refuse. The inventory was sold to Wausau Metals at scrap value and the rest of the company’s assets were purchased for $10,000.

In 1977, Wausau Metals started manufacturing metal blinds with two employees and a single piece of equipment. Not long after, Wausau’s former Venetian blind supplier, Royal Crest, of Toledo, Ohio, went bankrupt. Niederhofer bought the equipment at an auction, and set it up in the back of Milco’s new plant. Less than a year later, Niederhofer renamed the unit as Nanik Venetian Blind Company and placed its operations into the hands of Harry Colcord, a 27-year-old salesperson from Wausau Metals. Within three years, Nanik’s sales soared to $2.5 million.

In 1983, a new aluminum-coating facility was built – the venture was named Linetec. The increasing demand by architects for windows of different colors spawned Linetec. Wausau Metal’s existing facility included anodizing, but for any painted finish the division had to ship its extrusion to an outside firm. This niche was waiting to be filled, as hardly anyone was specializing in coating architectural products. Scott Platta, who had worked at Wausau Metals, Milco and Nanik headed Linetec and its 20 employees.

In 1985, Nanik broadened its product line by acquiring The Shuttery in Scottsdale, Arizona, a custom manufacturer of premium interior wood shutters. Buying The Shuttery meant the division was no longer just in the business of making Venetian blinds through Nanik, now it was in business of making window coverings, a broader, growing market.

Niederhofer resorted to his practice of splitting activities into smaller, more accountable profit centers by creating a free-standing group, Mini-Manufacturing in 1984, and Wausau Specialty Products in 1986.

By 1987, Wausau Metals had outgrown its 15-year-old anodizing line, and invested $4 million in a new automated line. Following a familiar pattern, the operation was named Anogee and set up as a separate free-standing profit center. It could then sell its capabilities internally and externally, like Nanik and Linetec had done.

By 1989, Harmon Glass consisted of 188 retail stores and 20 Glass Depot distribution centers in 25 states, becoming the second largest auto glass replacement chain and the largest replacement glazing company in the United States.